Are Ferrari’s specials truly a link between the racing cars of Gerhard Berger and Michael Schumacher and Fernando Alonso, and the road-going Ferraris one can buy? ‘Completely,’ says Fedeli. ‘They are exactly in the middle. There are the F1 cars, there are the GT cars, and in the middle we have these cars. We want to transfer the technology from racing to production and this is the way to do it. The concept of these cars is to put together all the innovations that we have. Not just one of two components, but everything that might become a component on our GT cars. They’re simply a forecast of the technology you’ll see across the range in the future.’

GTO

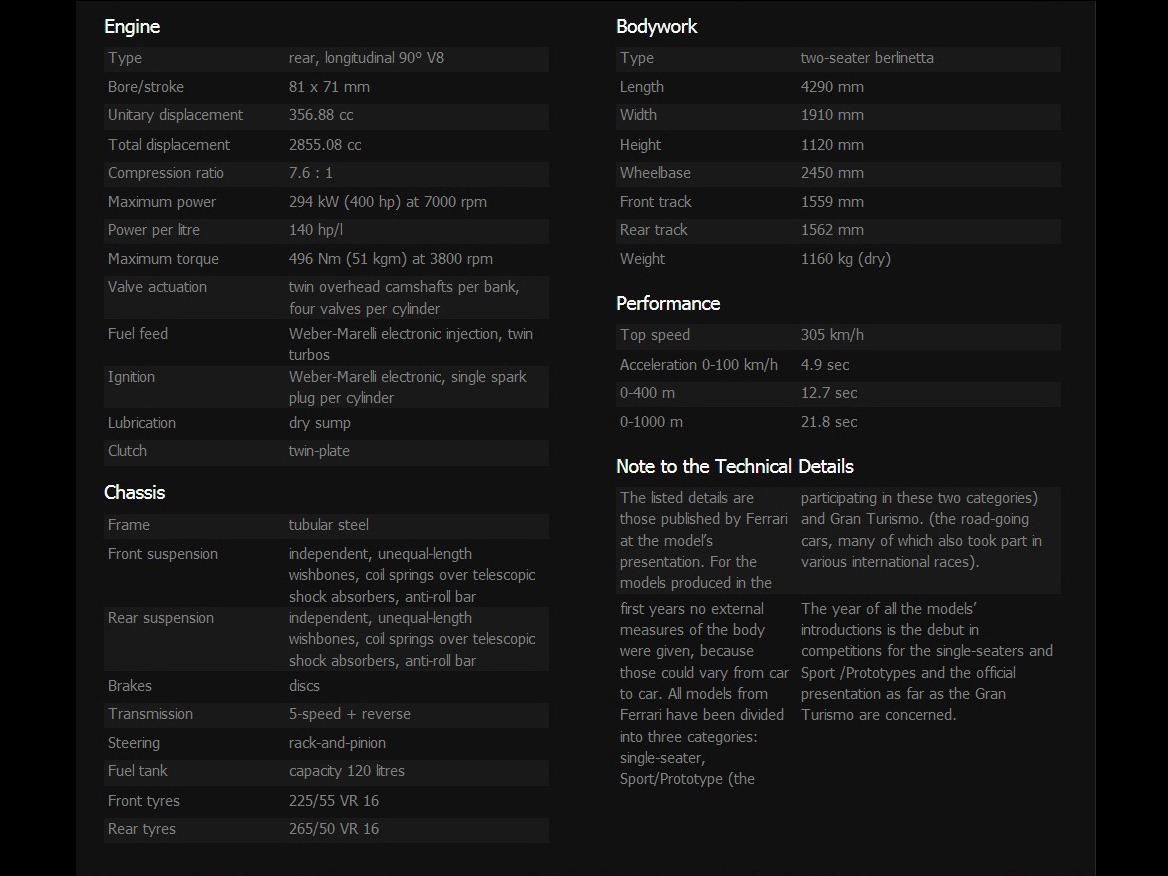

At the time of the GTO in 1984, the Gestione Sportiva was directly involved in development with the then Technical Director, Angelo Bellei, whose approach was identical to today. Bellei utilised F1 research, both for the chassis, working with Harvey Postlethwaite, and the engine, with Nicola Materazzi. ‘We applied pure F1 technology to two components in this car,’ Postlethwaite said, ‘and some principles to lots of body components.’ The 400hp, 2.8-litre V8 GTO differs from the other supercars in that it was designed to go racing, and not specifically as a road car. However, although the Group B category for which it was intended was cancelled, the 200 road-going examples required for homologation proved so beautiful to behold, and incandescent to drive, that 272 were made, and the GTO was instantly hailed as one of Maranello’s greatest-ever road cars.

The GTO marked the first use of plastic composites by Ferrari and it was significantly lighter than the 308 GTB on which it was based, despite being longer and wider, a theme that continues in its successors. Pininfarina’s legendary designer Leonardo Fioravanti added three gills to the bodyside at exactly the same angle as those of the 1962 250 GTO; they simply moved to the rear, along with the engine. However, for Manzoni, tasked with designing the latest special, the GTO also looks forward, and shares more with the Enzo and the new F150 than, for instance, the F50, which came in between.

‘The main difference if we compare this to the later cars is the lack of aerodynamic flaps or spoilers,’ he says. ‘Everything is very well integrated into the form, which is also our current approach. Even in an extreme car like the Enzo, there are no longer the spoilers of the F40 or F50. But back then, of course, it was normal to show in the form that this was the extreme of the Ferrari range. You cannot be too calm.’

Manzoni says the GTO is his favourite among the specials. ‘The proportions are fantastic. Maybe by today’s standards the wheels seem too small, but the whole design has a global equilibrium.’

The GTO marked the first use of plastic composites by Ferrari and it was significantly lighter than the 308 GTB on which it was based, despite being longer and wider, a theme that continues in its successors. Pininfarina’s legendary designer Leonardo Fioravanti added three gills to the bodyside at exactly the same angle as those of the 1962 250 GTO; they simply moved to the rear, along with the engine. However, for Manzoni, tasked with designing the latest special, the GTO also looks forward, and shares more with the Enzo and the new F150 than, for instance, the F50, which came in between.

‘The main difference if we compare this to the later cars is the lack of aerodynamic flaps or spoilers,’ he says. ‘Everything is very well integrated into the form, which is also our current approach. Even in an extreme car like the Enzo, there are no longer the spoilers of the F40 or F50. But back then, of course, it was normal to show in the form that this was the extreme of the Ferrari range. You cannot be too calm.’

Manzoni says the GTO is his favourite among the specials. ‘The proportions are fantastic. Maybe by today’s standards the wheels seem too small, but the whole design has a global equilibrium.’

F40

Just three years separated the GTO and F40, the shortest gap between specials, but even in this time the F40 clearly pushed at the technological limits again. Its power output was quite extreme - the 2.9-litre V8 with twin IHI turbochargers, now making 478hp - by the standards of the time and in a car of just 1,100kg.

Its greater use of Kevlar and carbon-fibre in the bodywork drew further on F1 practice and created a very different shape that allowed the F40 to be the first production car to break 200mph (320km/h). It was unusual for a Ferrari special to stay in production for five years from its 1987 launch, with a total of 1,315 made, more than all the other specials together.

This makes the F40 no less special. The fact that it was the last car created and launched under the auspices of Enzo Ferrari would always have ensured its significance. The fact that many rated it (and rate it still) as the most exhilarating road-going Ferrari to drive kept it in production then, and ensured values have remained high ever since.

Exhilarating – and challenging – Fedeli will plainly never forget his first experience in an F40. ‘I started at Ferrari when it was in its second year of production. My first experience of it was with a test driver at Fiorano. Even on the straights the steering wheel was never straight! But in that time the objective was different. Now it’s possible to fully appreciate the car immediately, without having to put it close to its limits. Then, you didn’t have the same technology to help get that result. The F40, F50 and Enzo are completely different to drive. The Enzo isn’t a difficult car to drive. You can manage its power without any problems. This is evolution.’

Nor did enthusiasts object to the F40’s spartan interior. ‘The interiors are very close to race cars,’ says Manzoni. ‘Even if we wanted to make them more sophisticated, we can’t. As with racing cars, we are constrained by weight. There are other objectives. But that focus becomes a value. The more race-car like the cabin is, the better.’

Its greater use of Kevlar and carbon-fibre in the bodywork drew further on F1 practice and created a very different shape that allowed the F40 to be the first production car to break 200mph (320km/h). It was unusual for a Ferrari special to stay in production for five years from its 1987 launch, with a total of 1,315 made, more than all the other specials together.

This makes the F40 no less special. The fact that it was the last car created and launched under the auspices of Enzo Ferrari would always have ensured its significance. The fact that many rated it (and rate it still) as the most exhilarating road-going Ferrari to drive kept it in production then, and ensured values have remained high ever since.

Exhilarating – and challenging – Fedeli will plainly never forget his first experience in an F40. ‘I started at Ferrari when it was in its second year of production. My first experience of it was with a test driver at Fiorano. Even on the straights the steering wheel was never straight! But in that time the objective was different. Now it’s possible to fully appreciate the car immediately, without having to put it close to its limits. Then, you didn’t have the same technology to help get that result. The F40, F50 and Enzo are completely different to drive. The Enzo isn’t a difficult car to drive. You can manage its power without any problems. This is evolution.’

Nor did enthusiasts object to the F40’s spartan interior. ‘The interiors are very close to race cars,’ says Manzoni. ‘Even if we wanted to make them more sophisticated, we can’t. As with racing cars, we are constrained by weight. There are other objectives. But that focus becomes a value. The more race-car like the cabin is, the better.’

F50

There was a longer wait for the next special, the F50 of 1995. But the evolution was greater. Rather than simply taking inspiration from F1, it took the extraordinary step of putting an F1 engine on the road for the first time, its 520hp, 4.7-litre, 60-valve, naturally-aspirated V12, based directly on the 1992 F92A F1 engine. And the F50 used a full Nomex and carbon-fibre tub where the engine was a stressed member, just like an F1 car.

‘The choice for us remains aluminium for our production cars,’ says Fedeli. ‘But the very low volumes of the special cars allows us to use carbon-fibre in the same way we do in F1, and when we do that, the weight we can save is significant. From a “body-in-black” point of view, the F150 is now very, very close to an F1 car.’

‘The F50 brings some elements of an F1 car to a road car,’ says Manzoni. ‘It was very clever in its treatment of the nose, the wing, the outlets around the nose. This became stronger and more iconic in the Enzo. If you imagine the Enzo without the fenders it really is like an F1.’

‘The choice for us remains aluminium for our production cars,’ says Fedeli. ‘But the very low volumes of the special cars allows us to use carbon-fibre in the same way we do in F1, and when we do that, the weight we can save is significant. From a “body-in-black” point of view, the F150 is now very, very close to an F1 car.’

‘The F50 brings some elements of an F1 car to a road car,’ says Manzoni. ‘It was very clever in its treatment of the nose, the wing, the outlets around the nose. This became stronger and more iconic in the Enzo. If you imagine the Enzo without the fenders it really is like an F1.’

Enzo Ferrari

The Enzo arrived in 2002, with the racing influence spreading to the six-speed paddle-shift gearbox the carbon-ceramic brakes, and active aerodynamics. ‘For an F1 car, aerodynamics means wings,’ says Fedeli. ‘That’s not the same for a Ferrari GT car, or a special car now. Starting with the Enzo we put away wings. We don’t like them from a styling point of view, but also for functionality. So, with the Enzo we developed some mobile devices to deliver the right loads at the right time. From a practical point of view, the aero on an F1 car is completely different from the one on a road car. But from the point of view of physics, the methodology, it’s completely the same, and the people who do it are the same, in the same way that we use the same algorithms for the brakes, the traction control, and the shock absorber controls in our F1 and road cars.’

‘The Enzo is still so modern and iconic,’ adds Manzoni. ‘You never forget it. And the new one must be even stronger. There is a rule in Ferrari that every new car must be completely new. Coming more than 10 years after the Enzo, the new car had to be a step into the future.’

‘The Enzo is still so modern and iconic,’ adds Manzoni. ‘You never forget it. And the new one must be even stronger. There is a rule in Ferrari that every new car must be completely new. Coming more than 10 years after the Enzo, the new car had to be a step into the future.’

F150

‘I wanted a front end still inspired by F1,’ continues Manzoni, ‘but not the same, so how to do it? Of course it’s not easy, but this is the most exciting project in the world! It was natural to create proposals, among which was to choose the most iconic, but at the same time futuristic and corresponding to the technical and aerodynamic requirements of the front end. There’s no comparison. This is the pinnacle of everything, of the aesthetics and technology of Ferrari. This always had to be a masterpiece.’

Fedeli, while respecting the heritage of the specials, is in no doubt about the F150’s significance. ‘The most important car is always the next one, and the F150 will be the Ferrari with the greatest transfer between F1 and a road car that we ever did. We are trying to anticipate the future with this car. We are trying hard to achieve the technical limit of every single component we are using, and also the packaging of the car as a whole. We are building a car close to the limits of technology, but we will only have succeeded if you can feel the result. The real objective of a special Ferrari is feeling, feeling, feeling.’

Fedeli, while respecting the heritage of the specials, is in no doubt about the F150’s significance. ‘The most important car is always the next one, and the F150 will be the Ferrari with the greatest transfer between F1 and a road car that we ever did. We are trying to anticipate the future with this car. We are trying hard to achieve the technical limit of every single component we are using, and also the packaging of the car as a whole. We are building a car close to the limits of technology, but we will only have succeeded if you can feel the result. The real objective of a special Ferrari is feeling, feeling, feeling.’

Architecture

A working group of F1 and GT engineers has been focused on the chassis for more than three years, availing itself of the contribution of Rory Byrne, who helped win 11 world titles in his role as the Scuderia’s Chief Designer. To achieve maximum efficiency and minimum weight, the carbon-fibre monocoque will be built in-house in Ferrari’s F1 composites department using materials, design methodologies, construction processes and instruments used to produce the single-seaters. Key to the chassis performance characteristics is the use of four different types of carbon-fibre which are hand-laminated then cured in autoclaves following engineering processes which optimise the design by integrating the different components. The result is torsional rigidity has increased by 27 per cent and beam stiffness by 22 per cent compared to the Enzo Ferrari.

The space beneath the bodywork has been cleverly utilised in order to house the complex mechanical units and to perfect the internal fluid dynamics. The positioning of the batteries and fuel tank assembly is key to this – just like on an F1 car, they are located in the safest, most protected part of the car and are set very low, just behind the driver’s back, to reduce the overall centre of gravity.

This was one of the key targets for the new car, along with a reduction in height and wheelbase to match that of the 458 Italia, despite featuring a V12 HY-KERS engine and dual-clutch gearbox.

The space beneath the bodywork has been cleverly utilised in order to house the complex mechanical units and to perfect the internal fluid dynamics. The positioning of the batteries and fuel tank assembly is key to this – just like on an F1 car, they are located in the safest, most protected part of the car and are set very low, just behind the driver’s back, to reduce the overall centre of gravity.

This was one of the key targets for the new car, along with a reduction in height and wheelbase to match that of the 458 Italia, despite featuring a V12 HY-KERS engine and dual-clutch gearbox.

Driving seat and position

In order to rationalise interior space, the cockpit, and consequently the entire vehicle, is built around the driver, making the most of Ferrari’s experience, both in functionality and ergonomics. Hence the decision to adopt a fixed seat, which will be made to measure (as it is in an F1 car), with an adjustable pedal box and steering wheel. The inclination of the backrest, and the fact that the occupant’s feet are at the same level as the driving position, gives an extraordinarily racy feeling and achieves a considerably lower centre of gravity.

Engine and kinetic energy

The F150 will be powered by a development of the 740 CV 6.3-litre V12 introduced in the new F12berlinetta, along with the latest evolution of Ferrari’s HY-KERS electric hybrid system unveiled at the Geneva Show in 2010. The HY-KERS system is a performance enhancer, as well as a tool in the battle to lower emissions. In fact, it is estimated that that the system shaves 10 per cent off the car’s 0-200 km/h time, while cutting emissions by an impressive 40 per cent, while also enhancing a torque vectoring system, traction control and brake force distribution as it is fully integrated with Ferrari’s already phenomenal chassis electronics. Under braking, the KERS directs the kinetic energy to charge the batteries.

The choice of battery size and weight is a fundamental factor in this type of technology. The amount of electric power that can be used, and how it is used on a car with these characteristics, are decisions that are made with an eye to performance, given the car’s natural vocation. However, a balance must be struck between the requirement for a battery that is not too heavy and the need for the supply of sufficient energy required for electric propulsion. The electric motor/ancillaries/battery unit has a weight-to-power ratio of one, a figure in line with F1 in terms of efficiency, thus further improving the car’s overall weight-to-power ratio.

The choice of battery size and weight is a fundamental factor in this type of technology. The amount of electric power that can be used, and how it is used on a car with these characteristics, are decisions that are made with an eye to performance, given the car’s natural vocation. However, a balance must be struck between the requirement for a battery that is not too heavy and the need for the supply of sufficient energy required for electric propulsion. The electric motor/ancillaries/battery unit has a weight-to-power ratio of one, a figure in line with F1 in terms of efficiency, thus further improving the car’s overall weight-to-power ratio.

Comments

Post a Comment